Teksti: Emma Nikander

Ancient DNA can reveal a lot about the history of people and the environment. At the same time, it can provide answers to some of today’s most pressing questions, such as biodiversity loss, climate change and pandemics.

The boring of sediment samples from the soil provides data from a very long time period: so long that it could not be accessed in any other way. For example, the deepest sediments of our 10,000-year-old Baltic Sea contain records of the sea’s whole history. Samples can be used to study the sea’s ancient and current organisms and to obtain information on the state of the environment during various periods.

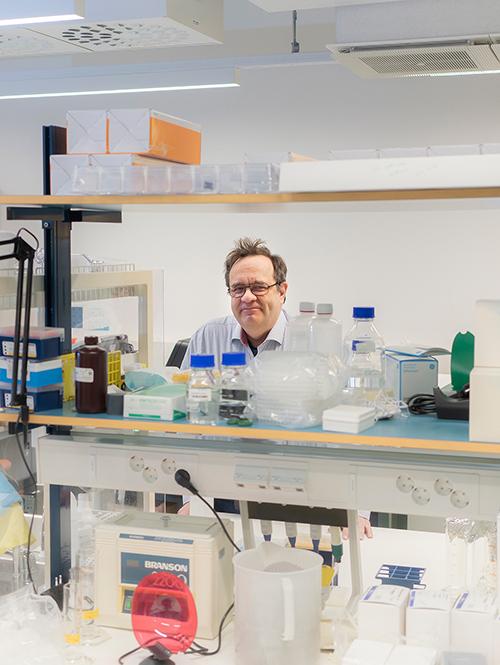

Geneticist Petri Auvinen and his team are running a project examining two types of samples that take them on a journey far back through time. In addition to sediment samples from the Baltic Sea, they are boring a second series of samples from a bog in Tammela, whose deepest parts can provide data on a similarly long period.

If DNA can be isolated from these samples, scientists can examine it for evidence of the historic microbes, flora and fauna of the region. The samples may also show what the soil was like and what happened to it when the climate changed.

This may help us to understand our current climate change, Auvinen explains: “It is easier to predict the future when you know what has happened in the past. Marine sediments and marshlands have been recording conditions for thousands of years without asking any questions. In this case, we can use history to reach into the future.”

What did the people buried at Levänluhta die of?

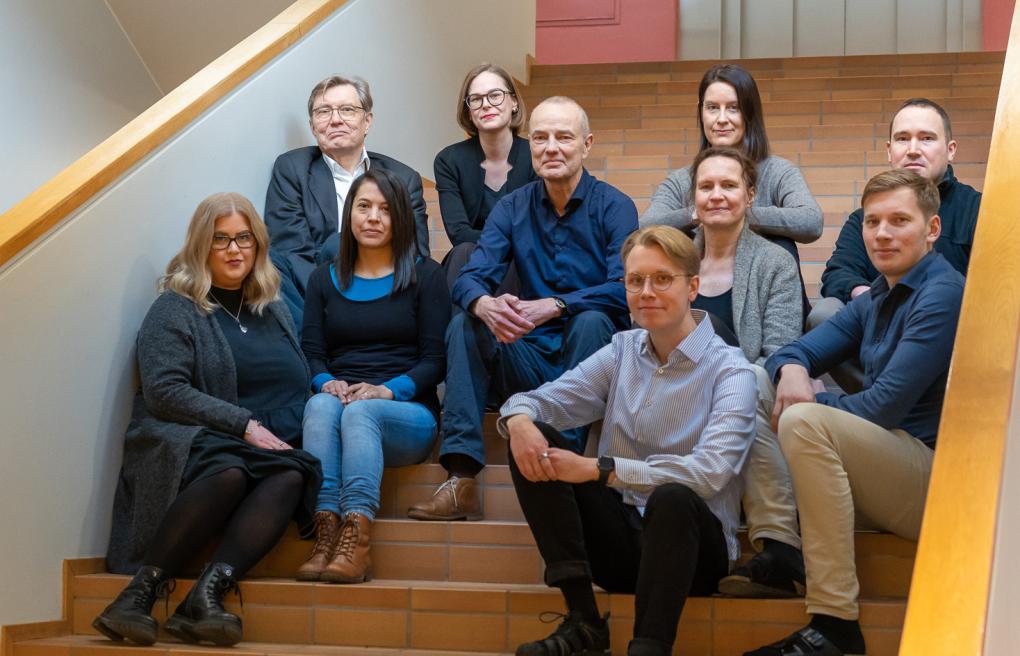

Studies of ancient DNA can also provide valuable information on people’s lives. A project conducted by Professor Antti Sajantila and his team is examining ancient DNA from remains recovered from two different kinds of burial sites from different periods. These are the tar pit grave in Ruukki, south of Oulu (northern Finland), and the waterlogged burial site of Levänluhta in Isokyrö (South Ostrobothnia) and the nearby Käldamäki burial site.

Besides the people who died, the team is interested in the viruses and bacteria they carried. By studying the human and pathogen DNA in the remains, the team is seeking to find out who the deceased were, what population group they belonged to and anything about their state of health or cause of death. They also want to know when the people lived and what they ate. Were they related? That can also be revealed using molecular research.

The Levänluhta burial site has been known since the 1670s, and it has been investigated using different methods for over a century. Diverse theories as to how the bodies ended up there have been suggested over the years, explains Professor Antti Sajantila of the University of Helsinki.

“The Ruukki area seems to be a burial site from a specific time period, whereas Levänluhta appears to contain remains spanning several centuries of the Iron Age. And not just human remains but also animal ones. Perhaps our research will show whether they died of an epidemic or of malnutrition, for example.”

The multidisciplinary research team includes experts in molecular genetics, forensic pathology, molecular virology and isotopes, as well as archaeologists. “Information produced by a single discipline would be significantly less valuable without the other fields to support it,” Sajantila says.

Data on the movements of hops and apples

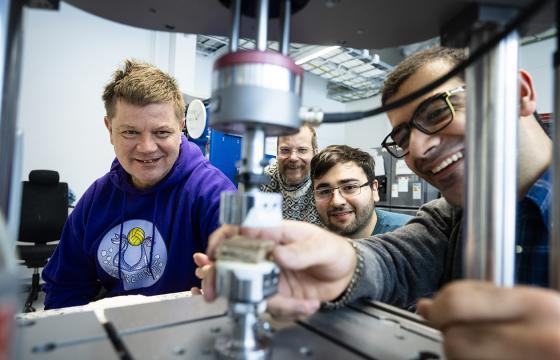

Information on ancient peoples and their ways is not only obtained by studying human DNA. Samples found at two archaeological sites – Stone Age Humppila and Medieval Turku Cathedral School in Finland – may generate data for example on the strains of hops and wild apple used in Finland. They are being studied by biologist Sanna Huttunen and her team at the University of Turku.

“We are trying to find out, among other things, what strains were used in various parts of Finland, are they related to today’s heritage or wild varieties, and how they spread,” Huttunen explains.

This information will then be compared with historical and modern data possessed by scientists at the Natural Resources Institute of Finland, Finland’s museums of natural history and individual researchers, among others, who are partnering with the project.

In Humppila (southern Finland), Stone Age strata have become buried in layers at the bottom of a paludified (filled-out) lake. The flora and fauna preserved in the peat can now be identified more accurately than before, using DNA barcoding. After that the team can examine whether they show evidence of settlement from 4,000 years ago. DNA methods can also be used to identify flora and animal remains that have previously not been recognised. This can show whether some of them were farmed grains, for example.

“That would be one of the earliest signs of agriculture in Finland,” explains the team’s archaeologist Mia Lempiäinen-Avci from the University of Turku.

Hops were very widely grown in the Middle Ages – almost by every household. Genetic data can show us how people spread various strains of the plant. Here, too, the past can help us equip for the future: if a specific strain of hops appears to have survived through the ages, it may have potential to cope well in the uncertain times ahead.

The samples are already in existence, so there is no need for new digs. Therefore the project will focus on examining them with microscopes and in labs, Huttunen explains. Every member of the multidisciplinary research team has their own areas of responsibility and expertise.

“The starting point for the research was that we have access to expertise and diverse data that can be seamlessly combined to achieve results that no one could produce by themselves.”

Demand for ancient DNA research

The 2022 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine went to biologist Svante Pääbo, who ran research that revealed the Neanderthal genome and led to the discovery of a whole new human species. The prize had a significant impact on the status of ancient, environmental and sedimentary DNA research, mentions Sajantila, who himself worked in Pääbo’s laboratory at one point.

Until now, ancient DNA research has lagged behind in Finland, and our extensive bodies of data have been under-researched, according to Lempiäinen-Avci. “I am thankful that the Finnish Cultural Foundation supports this highly necessary topic.”

“This kind of research teaches us to value our history and our special characteristics. All sorts of things may be revealed once we begin to examine data that has previously received little attention,” Huttunen explains.

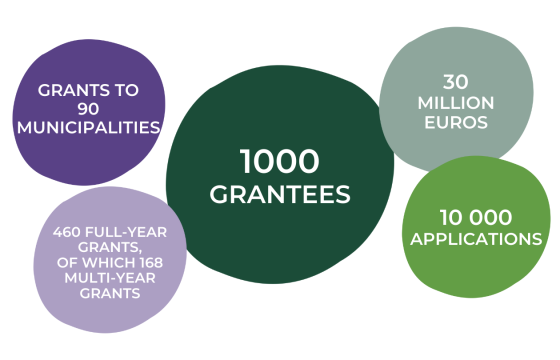

In 2023, the Finnish Cultural Foundation granted EUR 2 million in funding to research projects focusing on ancient, environmental and sedimentary DNA. The aim was to increase cooperation between research teams from various disciplines, thereby strengthening the field as a whole in Finland.