In the wake of colonialism

Helsinki-based sculptor Man Yau has, in just a few years, gained a position in the art world that many aspire to. Her works have been exhibited at institutions such as Kiasma and HAM Helsinki Art Museum, as well as in numerous galleries and museums abroad.

In January, Yau was awarded the nationally recognized art award, Young Artist of the Year. The recognition includes a €25,000 grant awarded by the City of Tampere and a solo exhibition opening this autumn at the Tampere Art Museum.

Working on the retrospective exhibition has required Yau to engage in self-reflection. The process gained momentum last autumn, when she spent three months at the Fabrikken residency in Copenhagen, made possible by the Finnish Cultural Foundation’s residency program. The new environment and culture inevitably led Yau to examine her own practice.

“The residency was a necessary reset for my artistic working methods. I also noticed that since art is talked about positively in Denmark, people respond to it in the same way. There were galleries on every street corner—it was fun to see and experience,” she says.

Challenging stereotypes

Yau earned her master’s degree from Aalto University in 2018 and graduated from the Academy of Fine Arts at the University of the Arts Helsinki in 2023. Her work explores issues of gender and identity, such as exoticization—a form of objectification where a racialized person is defined in relation to whiteness through stereotypes based on skin color or cultural background.

While her personal experiences and observations are at the root of her work, Yau finds it easier to approach these subjects through historical references. These include the European art trend Chinoiserie, which imitates and interprets Asian aesthetics through reductive stereotypes.

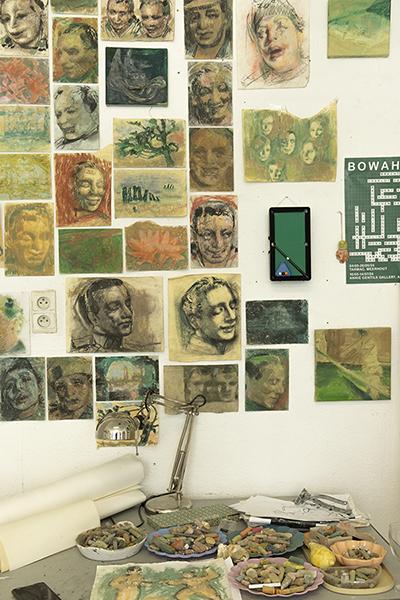

Yau initially gives a form to her ideas in clay, though the final work may be a bronze cast or a sculptural installation using mixed media. The creative process is time-consuming, often preceded by a long period of sketching and research.

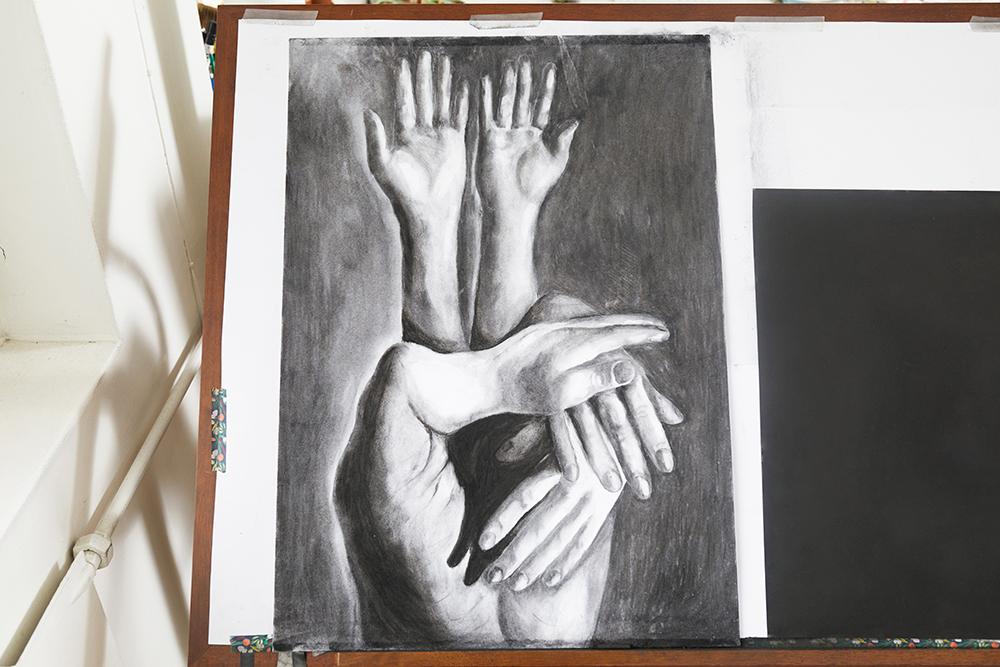

“I’m very physical, and plunging my hands into clay is a way for me to be present with the themes. Sometimes I just test and test and cry for hundreds of hours in the studio, until I suddenly realize what shape or tone, for example, the feeling of compression requires in order to express it,” she says.

Giving new form to the past

Yau chose Copenhagen for her residency to observe how Denmark’s colonial past manifests in everyday life. While there, she met a local sculptor whose job included maintaining the city’s numerous public statues—many of which are inspired by ancient Greek mythology.

“Aesthetic elements that stem from Ancient Greece and classicism are everywhere in Denmark. It’s fascinating, and at the same time deeply distressing, because of the history of the slave trade connected to it,” she says.

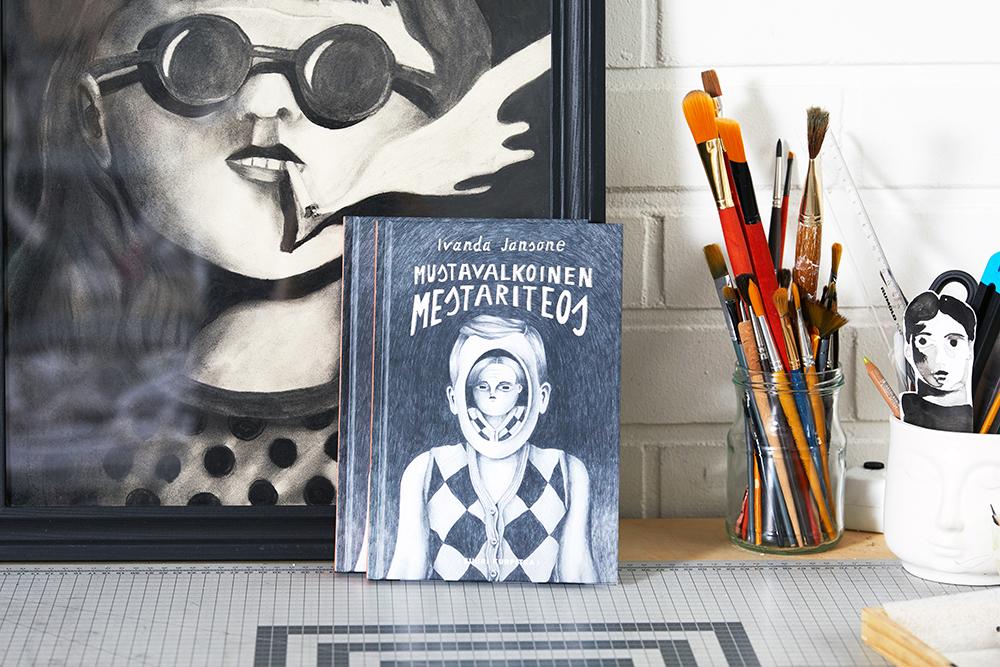

Among the many male deities, Yau found Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, who became the inspiration for a new series of works. The Artemis (arrows & quiver) installation features arrows made from Japanese Kyudo arrows and porcelain, and a quiver composed of ceramics, leather, and transfer images.

The work created at Fabrikken completes sculptures Yau made before the residency, including a porcelain suit of armor (Faux Bone China), a glass hat (Self-portrait), and bronze-cast shoes (Bow Boots). According to Yau, the new series was important because it brought the sculptural outfit to life.

“I wanted a classical aesthetic in the works, but at the same time the hand-shaped arrowheads resemble fisting sex toys. It gives the work a form that asks: who is really being penetrated, and who is the active participant?” says Yau.

Longing for slowness

Although Yau held her first exhibition 13 years ago, she has only gained national and international attention in recent years. This has been significant for her career, but the success has also brought conflicting feelings.

Interviews, photo shoots, and meetings inevitably take time away from making art, and the public visibility of her profession has exposed her to even sexist and racist hate mail.

“There are few opportunities and little funding in the art world, and only a handful receive recognition. I’ve never been luckier, but I can’t get started on my work because the pressure to succeed is so intense,” she says.

Next year, Yau will hold a solo exhibition at the Studio space of the Turku Art Museum. After that, she hopes to take a break from exhibitions—or at least slow down. A public art project would be a desirable next step, as it would necessarily involve a long process.

“I’ve always loved working slowly. I’d like to spend three years on a single piece, which was possible last time when I was still a student and no one wanted to show my work anywhere. I hope to find a project I can stay with so long that it starts to annoy me a little.”