Personalised data for preventing type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease

Nutrition scientists at the University of Eastern Finland are investigating whether genes affect who benefits from lifestyle changes and who doesn’t.

Text: Antti Kivimäki

Photos: Petri Jauhiainen

About half a million Finns have adult-onset (type 2) diabetes. Their risk of getting heart and blood vessel disorders is much higher than that of other people.

– Lifestyle changes can prevent or delay the onset of type 2 diabetes. This is known from very many studies from around the world, and there’s no need to investigate that any more, says Ursula Schwab, professor of nutrition therapy at the University of Eastern Finland, with a laugh.

– But these studies have not been able to observe the effect of hereditary factors. So do genes affect who benefits from lifestyle changes and who doesn’t?

This is what Schwab and her colleagues are investigating with the help of men from the city of Kuopio.

The longitudinal study Metabolic Syndrome in Men (METSIM), led by Professor Markku Laakso, has used interviews and measurements to follow more than 10,000 men randomly chosen from the Kuopio population register. The men were chosen from 2005 to 2010 when they were 45 to 73 years old.

Schwab and her colleagues chose 635 men from this cohort. Half of them have a high and half have a low genetic susceptibility to get type 2 diabetes.

– Today more than one hundred gene variants are known that cause susceptibility to type 2 diabetes, but when we chose the men in 2016, only 76 were known, so we created the groups based on these.

At first, there were group meetings for the men. Later, tips for exercising and health-promoting diets, such as high-fibre products and recommended dairy products, were offered more online.

– Previous comparable studies have focused on personal guidance. We wanted to now try what kind of effectiveness can be achieved with group and online guidance organised using less resources.

“Health-promoting lifestyles have also helped those whose genes cause a higher risk of getting lifestyle diseases. So here too, we’re expecting that lifestyle changes will help both groups similarly.”

What results does Schwab expect to get?

– According to previous studies, health-promoting lifestyles have also helped those whose genes cause a higher risk of getting lifestyle diseases. So here too, we’re expecting that lifestyle changes will help both groups similarly, says Schwab.

– But one can’t be sure before the results have been analysed. So we’ll wait patiently for what the results tell us.

***

In another, similar study, nutrition scientists at the University of Eastern Finland are investigating whether genetic susceptibility cause differences in how switching to recommended dietary fats affects the storage of fat in the liver.

One hundred men of whom half have the PNPLA3 gene variant that makes them susceptible to fatty liver disease were selected from the above-mentioned METSIM database. The PNPLA3 gene regulates fat storage.

The men were instructed to use soft vegetable fats instead of hard animal fats in their diets, and the study monitors whether there is a difference in the degree of fat storage in the liver depending on which variant of the PNPLA3 gene the men have.

– The PNPLA3 gene variant that predisposes to fatty liver disease is very treacherous since it simultaneously protects against type 2 diabetes. Often people with this variant don’t have high blood sugar or cholesterol levels, but their liver can be fatty. If fatty liver disease has progressed enough, it’s possible that nothing can be done anymore, Schwab explains.

Genetic studies are connected to the megatrend of personalised medicine in a broader sense. When genetic understanding increases, those in risk groups can get more personal advice.

In addition to working as a researcher, Schwab takes care of patients in the Kuopio University Hospital.

– Patients who have problems with blood fat levels often ask whether they can eat eggs. If I only knew whether they have a certain gene variant, I could answer more precisely than now. People who have this gene variant absorb dietary cholesterol well, so they are recommended to not eat more than three eggs per week. But others can eat eggs more freely, Schwab explains.

– Generally speaking, people could be more motivated to eat health-promoting nutrition if general recommendations were customised into personal recommendations that take into account their specific characteristics.

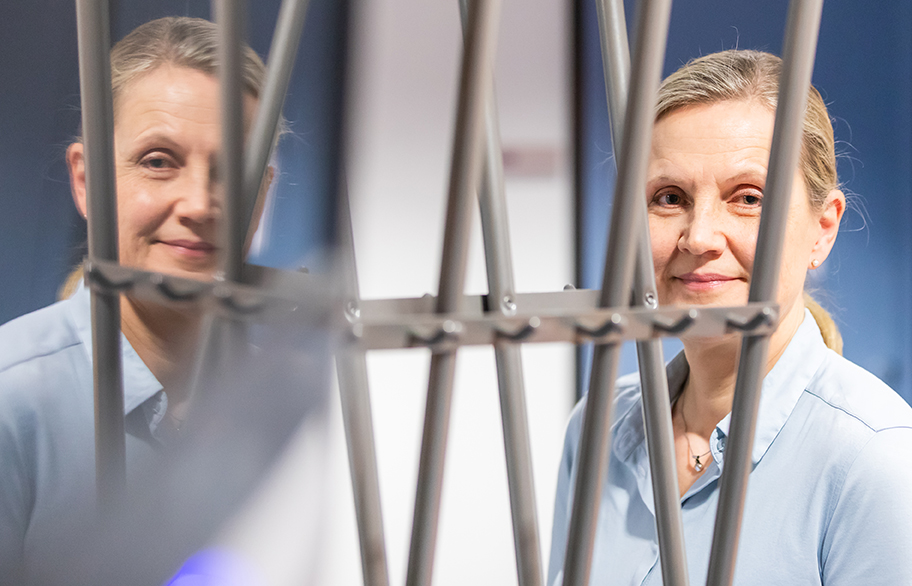

Professor of nutrition therapy Ursula Schwab and her research team at the University of Eastern Finland received 250,000 euros for research on the connection between genes and lifestyles in the prevention of lifestyle diseases.