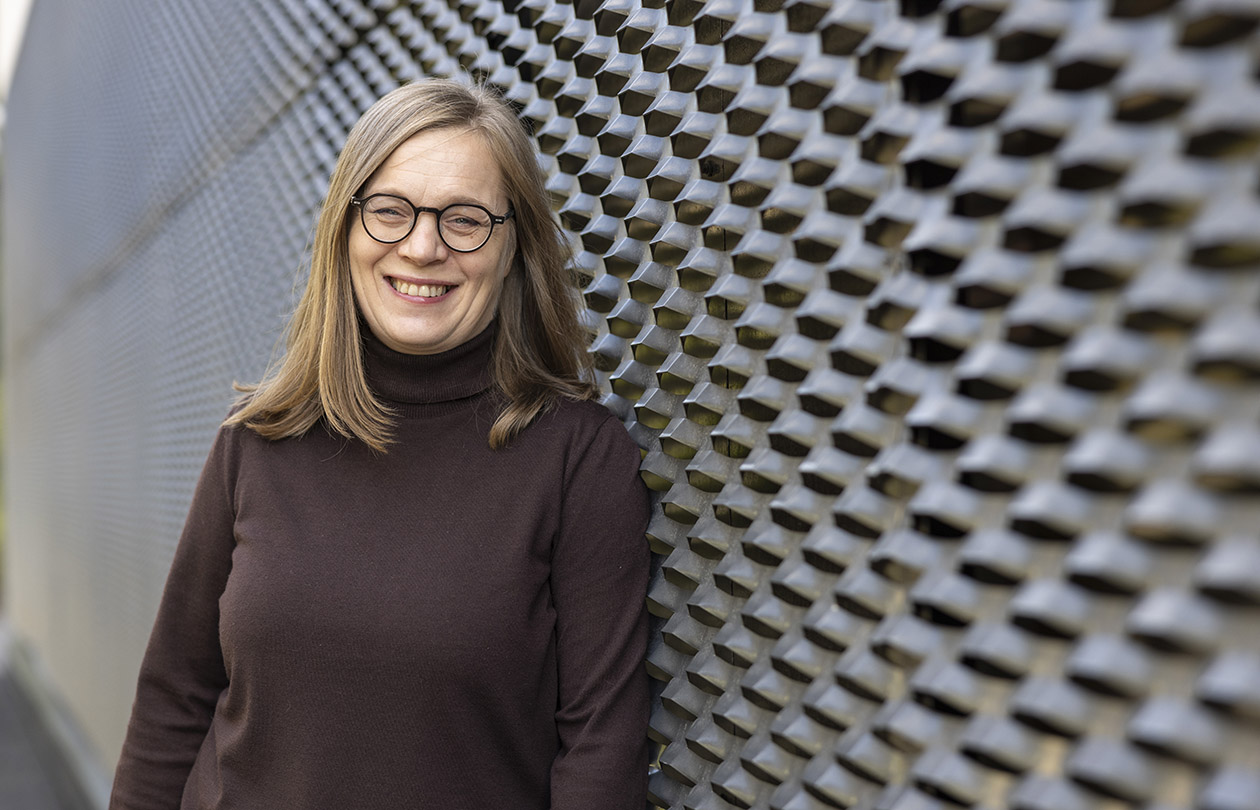

Plain-language literature is a step towards inclusivity

Fluent and critical literacy is a prerequisite for various ways of participating in society. Plain-language literature can provide encouragement, inspiration, and motivation, developing not only reading skills but also empathy and understanding.

In some situations, being able to read emergency exit can be a lifesaver. Hence reading can be considered a survival skill.

But it’s much more than just that. Minna Torppa, professor of educational sciences specialised in reading, writing, and learning difficulties at the University of Jyväskylä, notes that society in practice, and particularly in this day and age, runs on literacy. Everyday life, education, work, and the service system as well as keeping up with and taking part in society all require reading.

Reading isn’t just about understanding what different characters mean together as words, phrases, and sentences.

On top of basic reading skills, there are also functional reading skills, such as reading comprehension and combining and evaluating information.

“And then there are critical reading skills,” says Torppa. “It takes a fair bit of reading and knowledge to be able to search for, compare, and assess information and distinguish, for example, misinformation and disinformation or propaganda from accurate and reliable information.”

Concerns over weakening literacy

As literacy is a necessity, plain language can be seen as an act of equality. Torppa notes that particularly when it comes to public services, providing them in plain language is one way of ensuring inclusivity.

“Both the need for and challenge of clarity are particularly apparent, for example, in the communication of matters regarding legal texts. Legal texts are complex and precise, but instructions based on them must be clear and unambiguous so that the reader can understand them.”

Not only immigrants studying Finnish or people with learning difficulties benefit from plain language. According to the most recent PISA study, published late last year and measuring the skills of young people, the reading skills of Finnish youth had weakened significantly since the previous evaluation.

“When reading skills are weak, it can affect not only education and work but also everyday life in general.”

Torppa points out that the PISA study measures reading comprehension. She, too, is concerned by the results, as they also show a widening gap between strong and weak readers.

“We can no longer be proud of the number of weaker students being small in Finland in comparison to other countries. When reading skills are weak, it can affect not only education and work but also everyday life in general.”

The deterioration of reading skills has been partially blamed on difficulty in focusing on a task and lack of persistence to finish it. According to Torppa, research shows that there are links between attentiveness, perseverance, and reading. For example, reading and internalising lengthy instructions can be strenuous, if one has trouble concentrating.

Supporting self-efficacy

Plain-language literature provides easy access to practising and developing reading skills. When Finnish language skills are weak or it’s difficult to concentrate on a book, the threshold for reading a book in standard language might become too high.

Torppa talks about the experience of self-efficacy, which plays a significant role in what one decides to do. Self-efficacy arises not only from previous experiences but also from various internalised beliefs. Sometimes it’s based on a more certain knowledge, sometimes on assumptions that can be challenged.

“I don’t embark on a marathon because I don’t think I can do it. Similarly, someone won’t start reading a book because they believe it’s too difficult for them.”

Being able to read through a plain-language book proves that reading an entire book is possible. When reading gets easier, it usually becomes more interesting, and through more practice also reading skills start developing.

A pathway towards standard language

Plain-language books are often mentioned when schools are criticised for lowering their standards. Torppa understands the criticism, but she points out that not all literature needs to be written in plain language. If anything, plain-language books can be an introduction to the world of literature.

“Plain language can be a gateway to reading in standard language,” she says.

“Accessible plain-language literature enables a lot of things.”

The aim is to further study the motivating force plain-language books might possess. Literature isn’t only about acquiring and building up knowledge; it’s also deemed to develop empathy and emotional skills, as books can offer peer support as well as open new horizons and thus increase understanding of oneself and others.

Torppa emphasises that plain language shouldn’t replace standard language.

“But accessible plain-language literature enables a lot of things. It’ll be interesting to see how plain-language books are being used in schools, for example.”

The 80,000 plain-language books donated by the Finnish Cultural Foundation were introduced in Finnish secondary schools in the autumn of 2024, in response to concerns about the declining reading skills of young Finns and the continuing challenge for schools to make literature accessible to all.