History of Interest in Reading

Text: Reeta Holma

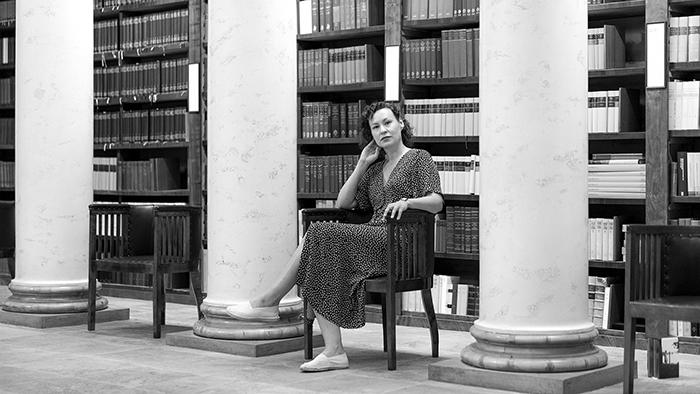

Photos: Petri Summanen

Tuija Laine (PhD, Theology) is researching Finnish people’s motivation for reading from the 1600s to the early 1900s. Even in those centuries, some people were more motivated to read than others. “I am interested in the factors that have influenced this,” Laine explains.

In her research, she is using some of the concepts of modern motivation studies. How have the needs for competence, autonomy and fellowship been fulfilled by reading and writing at various times, and what roles have these played in individuals’ motivations to read or write?

Even the peasantry were required to learn to read; it was a civic duty and a prerequisite for marriage.

The research subjects include some learned people, but the main emphasis is on common folk and children. Even the peasantry were required to learn to read; it was a civic duty and a prerequisite for marriage.

Being allowed to get married was a strong external motivator for literacy, but many other factors have also influenced people’s appetites for reading. Motivation increases if one is able to influence the content of one’s reading and if one feels capable. Community support is also important.

“References to disorders such as dyslexia can be found from earlier centuries, and even though they were not recognised as such, my materials indicate that they may have been linked to reading motivation.”

Laine’s background is in church history, specialising in the history of books. She wrote her thesis on the reception and translation of devotional literature, and has also researched bookselling and worked as a professor of book history. Laine was involved in the Finnish National Bibliography project.

Church record books as histories of reading culture

How is it possible to obtain information on people’s reading customs in history, when interviews are not an option?

“Church record books are an important source of information in Finland. They provide details on the development of literacy among individuals and their family members, and allow us to theorise on the factors that might have encouraged or discouraged people from reading,” Laine says.

The development of someone’s literacy may have been strongly impacted by life events, such as the death of their spouse.

Church records included information on who had attended literacy examinations and with what degree of success. Very personal, even tragic stories can be found therein; the development of someone’s literacy may have been strongly impacted by life events, such as the death of their spouse, for example.

Laine also has other sources. Some people were so well versed in reading and writing that they were able to tackle autobiographical writing. We also know about certain literacy-related practices, such as lessons given by the clergy and travelling schools. Textbooks provided guidance as to the most important factors in learning to read.

“Many of the things we now consider important aspects of literacy were already recognised centuries ago,” Laine says. Our understanding of them has only increased through modern-day research. The usefulness of music in learning was understood already in the Middle Ages, when texts and reading were taught through song. “Reading aloud has also long been known to further literacy and comprehension.”

History also opens perspectives into today’s debates on reading motivation – for instance concerns over boys’ lack of enthusiasm towards reading. “Reading has not disappeared from the world. We just have to find the right methods and means. When people find interesting texts and the right, encouraging social environment, they will read,” Laine says.

Associate Professor Tuija Laine (PhD, Theology) received a grant from the Eija and Yrjö Wirla Fund in 2020 for her postdoctoral research on Finns’ motivation for reading between the 1600s and 1900s.